|

Translating the physicality of the human body

into visual

representation has always been one of the crucial issues in the

history of western art, and one of the major concerns of artists and

philosophers of the early modern period. The discursive potential of

images concerning the human body encompassed essential categories of

knowledge, because they held the power of either reinforcing or

destabilising the very concept of the reliability of images, and thus

an entire cultural system which relied on the implicit truthfulness

of certain scientific, social and political notions. During the early

modern period, artists, physicians and natural philosophers were

engaged in furious debates regarding these questions, due to forceful

social shifts, extraordinary technological developments and a number

of discoveries occurring simultaneously in the geographical and

anatomical sphere.

This article focuses on a short series of

anatomical prints produced

by Giulio Bonasone, a Bolognese engraver, during the second half of

the sixteenth century. This collection deals with perceptions of the

body and its representation in untraditional ways. Bonasone was a

rather successful artist who worked in Bologna and Rome between 1531

and 1574, and who produced a vast number of engraving and a few

paintings.

In his catalogue Le Peintre Graveur, still an authority in the field

of early modern prints, Adam von Bartsch describes him as a

well-known engraver, prolific and inventive in his figurations but

not always consistent in the quality of his works.

This anatomical series was produced, according to Stefania Massari,

around the early ‘60s of the sixteenth century.

It presents, however, a number of odd, unprecedented features that

set it apart from the abundant production of anatomical studies of

that period. This collection, which comprises fourteen independent

engravings, has not yet been subjected to the analysis it deserves:

this article, then, aims to fill, at least partially, such gap. In

the limited space of this study, my analysis will not include all

images from the series. Rather, it will focus on a few prints that

assume a particular importance in the field of early modern

production and diffusion of knowledge about the human body and its

role in the natural world.

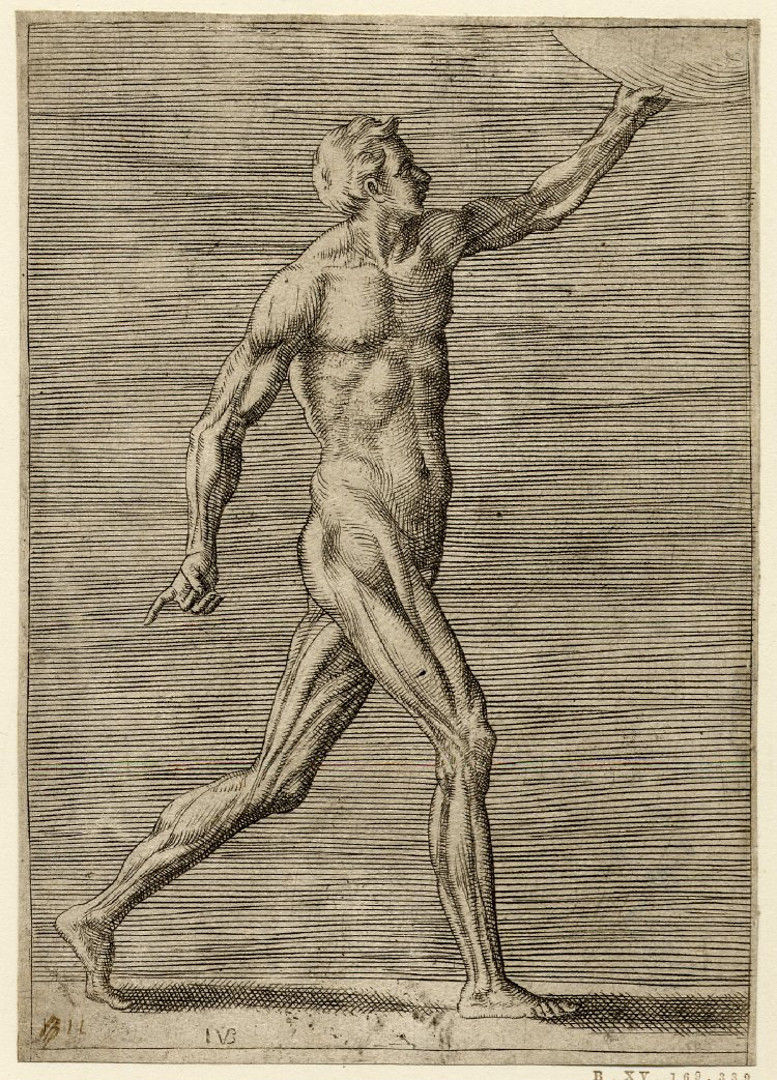

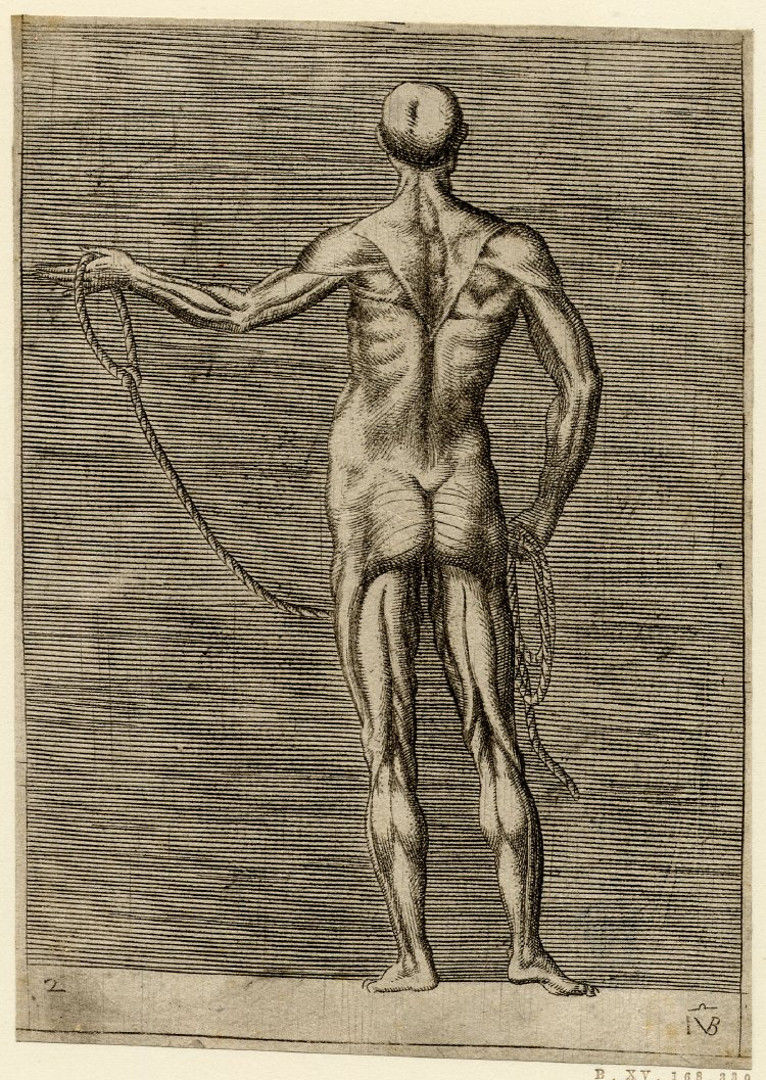

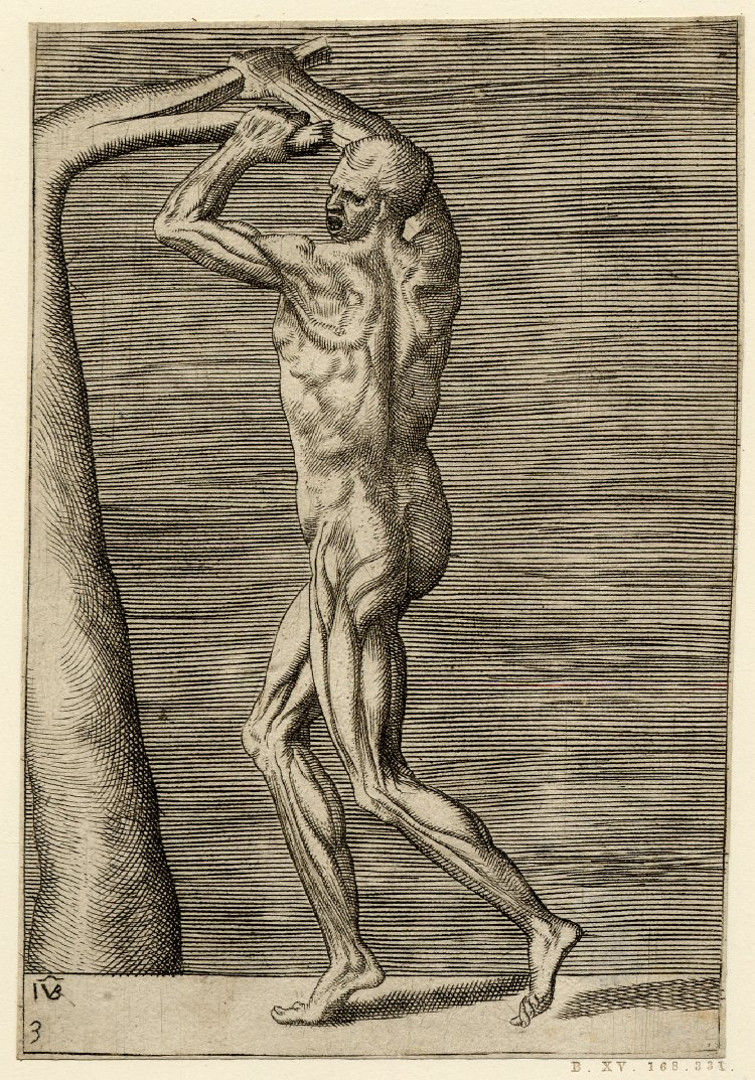

The peculiar qualities of these images is

immediately evident: in

each plate the figures interact with many different objects that are

ambiguous, or even extraneous to traditional visual vocabularies in

the representation of early modern anatomical illustrations (a globe,

ropes, a strange rectangular object, the branch of a dead tree).

(Fig. 1, 2, 3, 4) Many elements and themes present in more famous

images from the fifteenth and sixteenth century, such as the accurate

display of every muscle, organ and limb, or the insertion of the

human figure in some kind of natural or architectural environment,

are strangely absent. The bodies that inhabit these anatomical

illustrations exist in a space deprived of any sort of connotation,

precariously perched on flat, anonymous surfaces. More similar to

antique friezes than to images engraved on paper, each figure stands

out of a dull background made of thick dark lines.

In this article I will posit that these images,

rather than propose

an accurate representation of the human body which could be useful

for medical students, respond to complex social and psychic

implications that were (and still are) inextricably connected to the

violent act of dissection. In the early modern period, the body still

maintained its implicit value as image of God and ideal centre of the

universe: yet, it was on the way to become nothing more than mere

subject of cultural norms, legislations and restrictions. At the same

time, however, the body was starting to assume a crucial role for a

new production of knowledge: it is not casual that the Italian term

sviscerare means not only “to examine, explore, investigate”, but

also, quite literally, “to disembowel, lacerate, destroy”.

Annihilate the body, then, was necessary to know it. A similar

notion, which consequently materialised complex intellectual and

social tensions, was already present during the early modern period,

when the practice of dissecting corpses for didactic reasons was

progressively spreading throughout Europe.

Traditionally, early modern anatomical

illustrations expressed with

emphasis (bordering on the rhetorical) their own intellectual

authority. Thanks to a meticulous attention to detail and faithful

complementarity to textual apparatuses that generally accompanied

them, they claimed a reliability that depended from an absolute

adherence to natural forms. However, it is crucial to keep in mind

that the concept of anatomy as scientific discipline, and the very

notion of “science” itself, was foreign to cultures and practices

of the early modern period.

The ideas concerning nature and all its elements, including the human

body, were not arranged around unmovable categories: producing

knowledge was a fluid process, often based on more visual

representations than the establishing norms, laws and rules. The

artist’s imagination was not dependent from philosophical or

scientific systems, but, on the contrary, was an autonomous creative

tool, which retained its own authority.

One of the essential ideas in the production

and diffusion of this

kind of images was the assimilation of the human body to the divine

configuration of the entire universe. For this reason, illustrations

belonging to treatises of natural history and philosophy usually

represented the human (male) body as an idealised model, the most

complete and perfected expression of nature.

Such a notion combined religious dogmas with influential texts and

philosophies from classical times, among which the famous statement

by Protagoras that “man is the measure of all things”. When

looking at the figures from Giulio Bonasone’s series, it is evident

how the main focal point of these engravings is the variety of

motions, gestures and animations, rather than an idealised

representation of the body. The distorted, extreme facial

expressions, as well as the forced and contrived rendition of the

muscles, indicate a very different purpose. To fully appreciate the

uniqueness of these images, however, it is necessary to contextualise

them in contemporary developments concerning the study of the human

body.

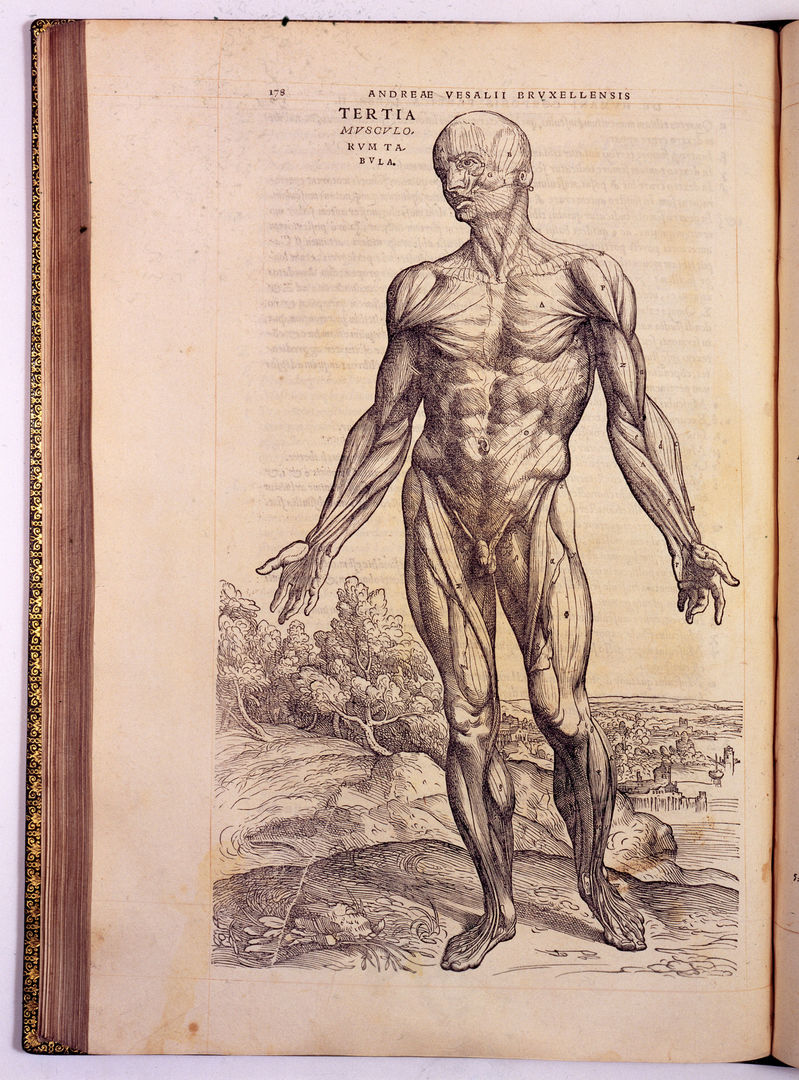

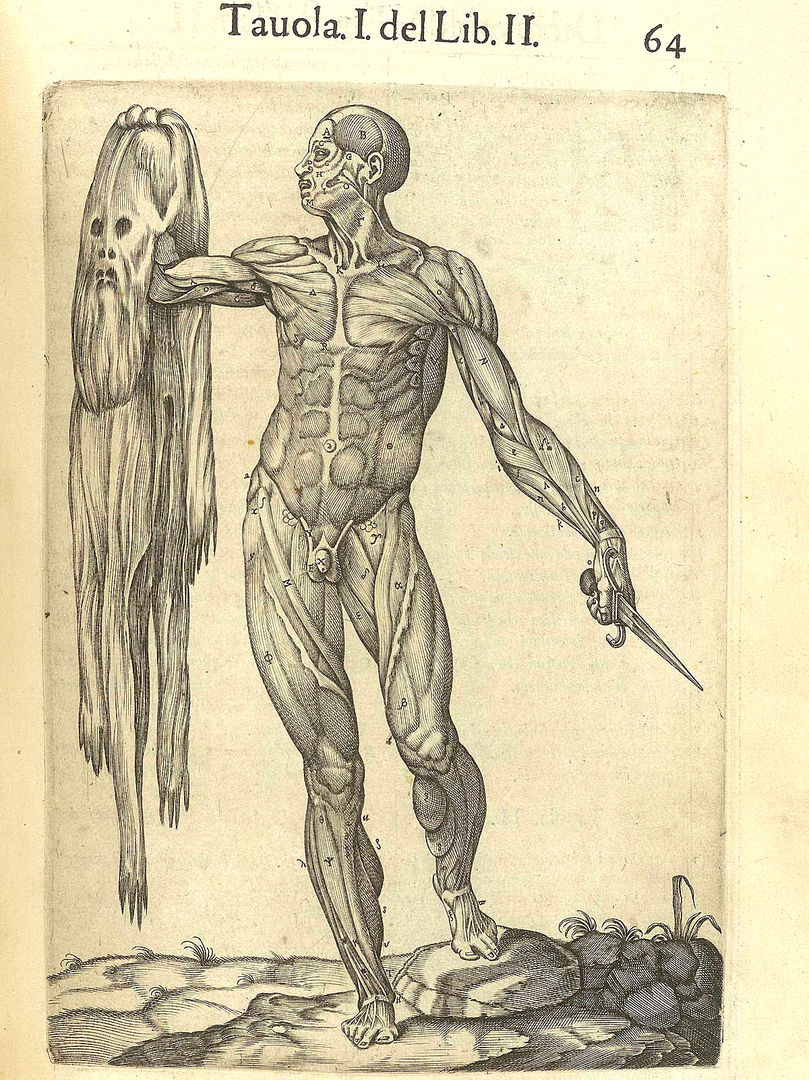

The publication of the seven volumes of the

Fabric of the Human Body

by Andreas Vesalius in 1543 represented, as it is commonly known, a

breakthrough in the modes of perception and representation of the

body. (Fig. 5) This treatise on human anatomy included original

illustrations, richly detailed and directly related to the textual

body (relying on the use of cartouches, inscriptions, annotations).

The Fabric developed and promoted not only an innovative system of

practices related to medicine and the exploration of the body during

dissections, but also a new epistemology based on the human body,

which aimed to find common norms and rule to compensate the (often

troubling) variety of corporeal differences. As I have already

mentioned, the problems inherent in the search for reliability and

truthfulness when reproducing the natural world in image assumed in

the early modern period an even more urgent quality in relation to

the body. These representations epitomised and influenced the

production and diffusion of anatomical knowledge just as much as

contemporary medical discoveries, so that notions of dissection and

personal identity soon became interconnected, if not mutually

dependant.

The innovations brought forth by the Fabric

consisted not simply in

the correction of a few mistakes in Galen’s system of physiology,

to an extent already known but still part of a rigidly solidified

medical knowledge. Rather, as Andrea Carlino argued in his Books of

the Body, Vesalius proposed a new research methodology, through which

he both reinforced the didactic potential of dissection and

introduced a tool for a critical and empirical knowledge of the body,

independent from classical texts.

Vesalius had been the first to realise how practices of dissection

were the only possible guide for a reliable description of the human

body. The method he proposed was at the same time didactic and

investigative, so that body and text worked together to express this

new knowledge. From the Fabric transpires thus a particular emphasis

on the importance of combining visual representations with more

abstract teachings and investigations.

Bonasone’s anatomical engravings, as opposed to

the ones in

Vesalius’ treatise, were not produced for comparative or analytic

studies of the human body. The figures, roughly sketched and

seemingly assembled more at random than following methodical studies,

could not be further away from the normative intent of the Fabric.

While, in Vesalius’ treatise, illustrations follow one another in a

progressive unveiling of the body and its insides, in a path of

discovery parallel to the physical act of reading the book (where

pages become a metaphor for skin, muscles, bones), Bonasone’s

series follows no such methodological device.

It is significant that Bonasone’s engravings

are not referencing

any kind of text. Rather than codifying specific norms and producing

precise, quantifiable information or data, these figures prefer to

communicate with the viewer in more immediate ways, through gestures,

postures and facial expressions. The sense of unease that imbues

these images originates precisely from this non-verbal quality. Of

course, the enigmatic, impenetrable and somewhat macabre atmosphere

of these illustrations belongs to many other early modern

representations of dissections (such as the prints by Charles

Estienne and William Harvey). They all represent, in different ways,

the same nightmarish vision of a corpse coming back to life,

obscenely displaying its muscles, tendons and bones.

Giorgio Agamben argues, in his essay Nudities,

that the desire to

show one’s own flesh, to force the body in incongruous and trivial

positions, is a psychic strategy that aims to destabilise and disavow

the divine essence to which the body, both in theological and

psychoanalytic fields, is inextricably connected. What is revealed,

in these contrived postures, is the explicit and irreparable loss of

this state of grace.

The naked body (and thus also the anatomised body, since the extreme

point of nudity is the one where not only clothes are removed, but

skin itself) as symbol of knowledge refers to philosophico-mystical

discourses, because it embodies precisely the process of discovery,

the appropriation of a specific discourse of knowledge. We are

particularly fascinated by such images, Agamben posits, because they

do not represent reality, the thing, the object, but the essential

possibility to be aware of it, to understand it.

It is then from representations of the body

that it is possible to

extract a more insightful anatomical knowledge. This intuition, with

its somewhat exoteric taste, seems to reverberate in the images I

have discussed so far, precisely due to the way they reproduce and

make the body visible. The figures are situated in a more abstract

and intellectual context, where knowledge is not merely transmitted

but actively created. The links between figures and text, references

to classical art, allegorical themes, natural landscapes and

architectonical ruins are not merely stylistic details, but

iconographical tools that aim to reinforce a specific notion of the

human figure. All these devices contribute not only to the production

and dissemination of ideas on the importance of anatomical studies

(drawing on authoritative classical culture), but also, perhaps, to

mediate between the desire of knowledge and the anguish and guilt

generated by the physical act of dissection, after all still a

heavily stigmatised practice.

Both in Italy and in Europe, corpses were

anatomised in a theatrical

setting, during performances that had strong liturgical undertones.

Anatomy as a practice was subjected to rapid changes: from private

lessons for students of medicine and surgery, it was quickly

transforming into a public spectacle, open to a wide range of

individuals (artists, craftsmen, even casual spectators).

The ritualistic aspect of human dissection, a solemn combination of

public punishment and production of knowledge, norms, conventions, is

a fundamental aspect in early modern culture, and plays an important

role in both the analysis and the understanding of anatomical

representations. As Jonathan Sawday argued in his seminal book The

Body Emblazoned, published in 1995, such dramatic performances merged

theatrical practices, bio-political demonstrations of judicial power,

and philosophical allusions to the divine origin of the human body,

with all its theological implications.

As Sawday points out, the issues of crime and punishment were

inextricably intertwined into many aspects of early modern Italian

culture. Dissection as capital punishment was an established practice

in Italy by the second half of the thirteenth century. It was

designed not only to evoke terror at the idea of the violation of the

body, but also to add another, much more horrifying dimension to the

already harsh sentence: the denial of a Christian burial, which

involved the posthumous – and eternal – punishment of the

criminal’s soul, thus unable to access Heaven.

Moreover, the stigma associated with public dissection also lied in

the dramatic violation of personal and family honour and the

humiliation derived from the public exposure of the naked body.

These issues were definitely present in the minds of artists who

worked on anatomical illustrations, and provoked intense emotive

reactions that emerged in different ways in their production.

It is very likely that Giulio Bonasone himself

assisted to such

spectacles in the renowned anatomical theatre of Bologna. After all,

studying human proportions and acquiring first-hand experience of

human bones, muscles and skin, was considered the mandatory approach

for those who wished to learn how to correctly represent the human

body. It was first Lorenzo Ghiberti in his Commentarii of 1447 to

state that

“It is necessary [for the artist] to have seen

anatomy, so that the

sculptor knows how many bones are in the human body when sculpting a

male statue, and how many muscles are in the body and all the nerves

and ligatures are in it”.

The importance of such statement should not be

underplayed: however,

similar ideas already existed in essence, as Leon Battista Alberti

attests. In his treatise De Pictura of 1435, he advised painters to

represent the nude body drawing the bones first, then the flesh, and

finally the skin, thus assuming that artists had some prior knowledge

of human anatomy.

It is now common knowledge that already in the early sixteenth

century the study of anatomy as a didactic practice for artists was

firmly positioned among the practices of “bella maniera”,

especially after Leonardo’s and Michelangelo’s progresses in the

study of the realistic composition of human figures. Countless

studies of single bones, limbs and muscles remain to us as a proof of

how widespread such anatomical practices were in that period.

The punitive act of flaying was another

practice associated not only

to the study of anatomy and the judiciary system, but also to

artistic activities. According to early modern scholars such as Sarah

Kay, removing the skin as punishment was not only a recourse of law

but also a form of “poetic” or moral justice. While it was

instigated as sentence, it could be reversed into – and even

embraced as – a sort of Christian sacrifice, situating the criminal

in a kind of christological dimension. Thus, the extreme suffering of

such physical and intellectual torture, (since it encompassed

physical pain and definitive loss of identity) could be sublimated

into an abstract, almost spiritual invulnerability.

An interesting detail in relation to the link

between punishment and

anatomy is that each lesson at the anatomical theatre of Bologna

would begin with the formulaic expression “our subject for the

anatomy lesson has been hanged”.

The recurring presence of ropes in Bonasone’s anatomical images

seems to be an explicit reference to this dense culture of

punishment, shame and ritual. It is surprising to notice the almost

insolent attitude of the figure in Plate 2 (Fig. 2) who resolutely

turns away from the viewer. It is as if the corpse is evoking,

through a deliberate denial of eye contact, its own identity loss,

its reduction from man, created in the image of God, to object of

study, no more dominating nature but simply a part of it.

The dual state of the body, stuck between

sacredness and materiality,

seems to be epitomised in Plate 14, (Fig. 3) in which the figure is

literally split in half: on one side, it is still fully fleshed, on

the other only bones remain. Such a figuration was already on the way

to become a common trope in early modern anatomical images, not only

because it offers a comprehensive picture of how bones influence the

motions of the muscles,

but also because it acted as reference to allegorical and

philosophical concepts concerning the temporary nature of the body.

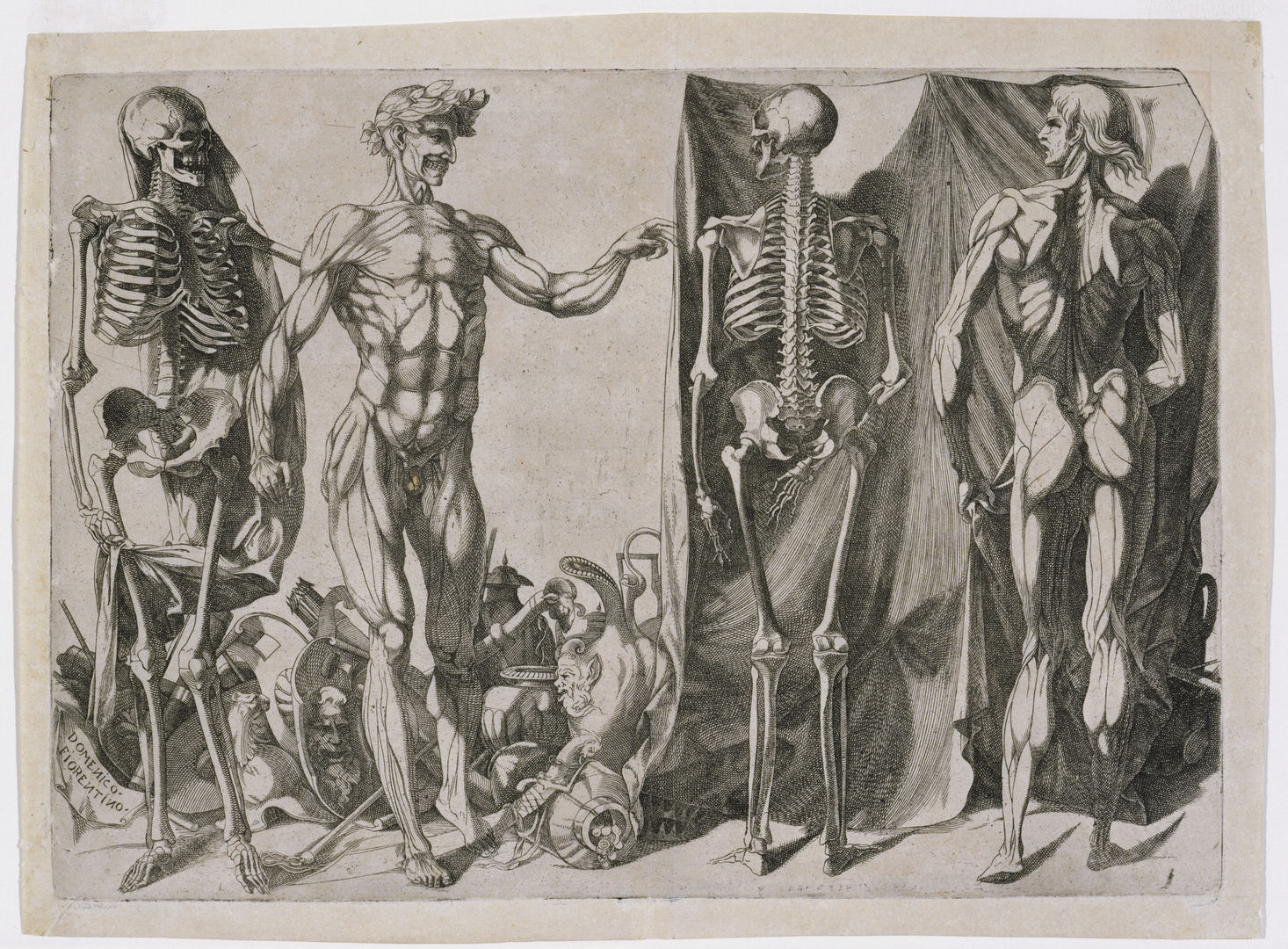

An example of this trend appears, for instance, in an engraving

produced by Domenico del Barbiere after a drawing by Rosso

Fiorentino. (Fig. 6) In this image, two écorchés (flayed bodies)

and two skeletons are showed simultaneously: the exasperated details

in the representation of the muscles and the stretched, unnatural

poses of the bodies reflect the visual vocabulary of the contemporary

mannerist style. The details of the trophies and battle vestiges are

easily recognisable as allegorical references to the ephemeral value

of life’s accomplishments and glories. The mysterious dark curtain

on the right and the cloth that covers the skeleton on the left,

almost a parody of the laurel crown on the head of his flayed

companion, are most likely allusions to the inevitability of death.

In Bonasone’s engravings, however, such allegorical references are

accurately avoided. Moreover, if compared to Domenico del Barbiere’s

skeleton, the one in Plate 14 (Fig. 3) is outlined with scarce

attention to physical accuracy, especially in the detail of the right

hand, which seems still be covered in flesh. The focus is clearly on

the emphatic, demonstrative gesture of the right arm. The enigmatic

rectangular object on which his left hand is posed, maybe a column or

even a stylised tree trunk, contributes to the general feel of

incongruity. But it is perhaps the detail of the facial expression

that generates the gloomy sense of loss and dread that imbues this

engraving. The mouth, open as if emitting a constant lament, and the

eyelids, lowered or maybe open on hollow eye cavities, transform this

figure from a rigorous technical illustration into a terrible vision

from Hell.

Whoever dealt with bodies and their

representations was certainly

well aware of the discursive relationship between the incisions

artists made on metal plaques to produce images and those made on

cadavers during dissections. Prints, easily accessible and

reproducible on a large scale, became in the early modern the

favourite mode of transmission and diffusion of anatomical knowledge,

eventually creating a well-defined style with its own conventions and

recurrent representations. Engraving, a highly skilled craft

characterised by a lengthy process and an uncertain result, was

conceived in consideration of the materials it employs, its nature,

resources and potentialities. Since the medieval period, it was

common to consider the medium, in this case a metal plaque, as a

bearer of a specific meaning per se.

The similarities between the act of peeling the paper from the plate

and ripping the skin from the body could not have passed unnoticed.

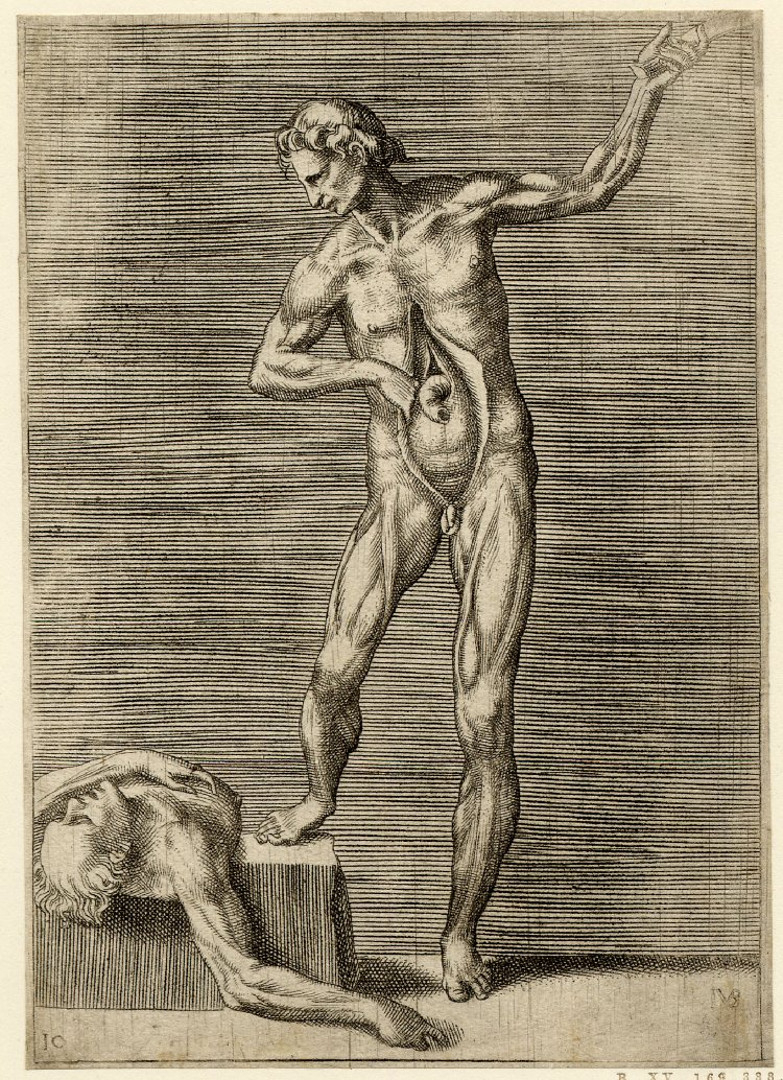

Plate 11 of Giulio Bonasone’s anatomical

collection (Fig. 1) shows

a figure holding an object similar to a globe

placed in the upper right angle. Yet, both the pose and the odd

shadowing seem to leave space for another interpretation, one that

takes into account the intersections between engraving and dissecting

the body. In this image, it appears the flayed body is grabbing the

folded angle of the very page it is engraved onto. As the anatomist

strips the skin from a dead body, to discover the inner functions of

a still mysterious organism, so the engraver strips the paper from

the metal plaque to unveil the newly created image, a new site of

knowledge. The skinless corpse seems to be removing another layer of

skin, the layer of the page imprinted on the metal plate, as if

mirroring the same procedures it has been subjected to.

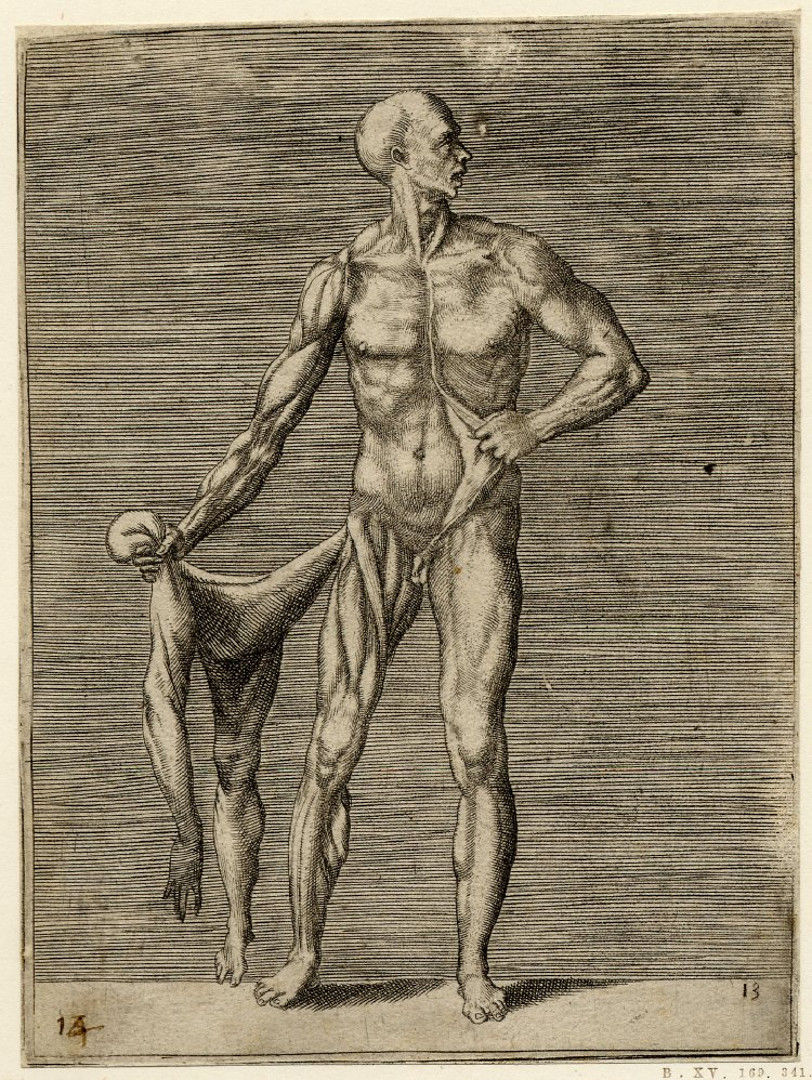

Other images in this collection, such as for

instance Plate 13, (Fig.

7) represent the corpse removing its own skin and holding it as if it

were a cloth or a cloak. Sarah Kay posits that this figuration was

made common by devotional representations of Saint Bartholomew, such

as that in Michelangelo’s Final Judgement in the Sistine Chapel.

More than a popular way of producing images, however, depicting a

corpse flaying itself was both a way to display the features of each

muscle while preserving the unity of the human body, and a strategy

that triggers a deep affective and visceral response.

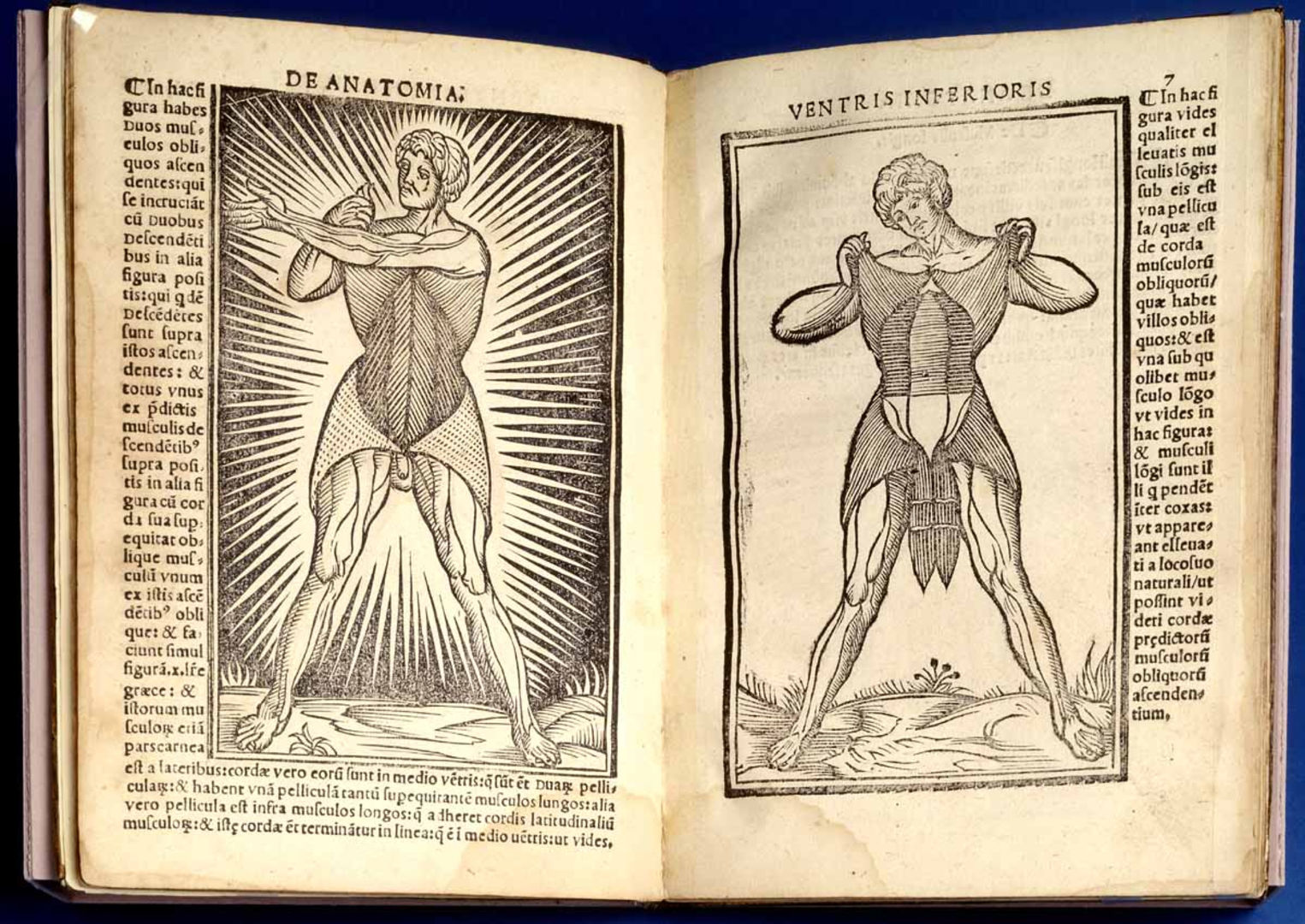

Self-anatomising corpses populate not only the pages of Vesalius’

Fabric, but appear in the vast majority of texts, even from earlier

times, concerning the body. They are featured, for instance, in

Berengario da Carpi’s Isagogae breves in anatomiam humani corporis,

a medicine treatise published in Bologna in 1523 (Fig. 8) and in

books as famous as the Fabric, such as the immensely popular Historia

de la composicion del cuerpo humano by the spaniard Juan Valverde de

Amusco, printed in Rome in 1556. (Fig. 9) Somewhat in between

plagiarism and genuine attempt of improvement, Valverde famously

borrowed almost the entirety of Vesalius’ illustrations (without

acknowledging his authorship) in some cases combining them together

to produce particularly insightful images, which represent even today

a fertile terrain for the study of early modern practices related to

the body.

In these anatomical illustrations, skin is no

longer perceived as a

mere surface, but becomes instead a more productive site onto which

political, cultural and psychic issues are projected. As it has been

pointed out, the fact that skin (or its representations) can mean at

the same time beauty and abjection, and evoke both attraction and

repulsion, highlights the skin’s potential to bear multiple and at

times contradictory meanings.

And contradictions and ambiguity seem to propagate from body to

printed space in Plate 13. (Fig. 7) The figure’s shadow does not

dissolve into emptiness: instead, it stops abruptly when meeting the

background, suggesting the association of the printed figure to

statuary reliefs. The corpse is represented in the process of

tearing his skin apart, so that its body appears, once again,

splitting in half: one side is still enveloped by skin, while the

other exposes its insides. An uncanny shadow of that same body,

however, seems to emerge from the lump of skin he is holding in his

right hand. An inert mass, somewhat elongated, this formless sack of

skin is transformed into a smaller scale double of the body it comes

from. The skin from the corpse’s arm, slightly twisted, assumes the

shape of a leg. The skin removed from the right leg, instead,

maintains its form, and clearly mirrors the one made of flesh. There

is no encounter nor exchange in this figuration. In what seems like a

refusal to acknowledge his own fragmentation, its dissociation, the

corpse forcefully turns his head away from his double, a shadow of

himself made of dangling skin, enclosing emptiness. Removing skin

brings about a brutal elimination of personal identity, because it

unveils one of the most troubling displacements of the human psyche:

situating the essence of the self not inside the body, but on the

skin, its enclosing layer.

In anatomical images, the body is an individual

entity that can be

scrutinised, rationalised, normalized, so that the split, the

doubling, happens between the fleshy materiality of the body and the

intangible idea of consciousness, of individuality, a site of

knowledge production. The body is, in the images by Bonasone,

something to colonise through mental abstraction, and it becomes a

territorialised representation of the space in which anatomisation

happens. As Didier Anzieu notes in his book The Skin Ego of 1985,

skin functions in a paradoxical way, since it is a form of identity

that we perceive in modes that are simultaneously opposite: permeable

and impermeable, superficial and profound, truthful and misleading,

source of pleasure and pain.

Considering those elements in reference to anatomical art, in which

“phantasies of mutilation of the skin have been freely expressed”,

Anzieu concludes that painters, much earlier than writers and

psychoanalysts, “perceived and represented the link between skin

and perverse masochism”.

The theme of inflicting pain in ourselves and to others is explicitly

expressed in Plate 10, (Fig. 10) in which a male figure lies dead at

the feet of another, partially flayed and holding a knife. This image

represents an original response to the social discourses and

iconographical conventions discussed so far. If the trope of the

self-dissecting corpse was already part of an established visual

culture, the paradoxical splitting between victim and executioner had

never been expressed with such clarity. This illustration seems to

embody (pun intended) such processes of physical and psychic

fragmentation. In Vesalius’ treatise it is the same body to be

represented over and over, page after page, removing each time a new

layer, from skin to bone. This figuration, instead, doubles the body,

seeking new meanings by destabilising the notion of individual

identity and corporeal integrity.

As I have already mentioned, representing

corpses of criminals as

initiators of their own dissection was a strategy to complicate the

rituals surrounding crime and punishment. Through self-dissection,

these figures internalise the punitive act, since they give in to the

social obligation to produce anatomical knowledge; yet, at the same

time, they resist to penal codes of the early modern age, because it

is from them that this knowledge depends.

In Plate 10, (Fig. 10) the course of the events is unclear: the plate

could represent a murder scene, perhaps a re-enactment of the

criminal act committed by the anatomised body in life that eventually

led to his punitive dissection. Or, conversely, we could be seeing

the same figure at two different moments in time: the self-flaying

man prefiguring the fate (his life-after-death, as purveyor of

knowledge) of the one lying lifeless on the pedestal. Such an image,

complicating the narrative of dissection, would certainly appear less

disturbing were the two bodies represented separately (as they are in

Vesalius’ Fabric). Pairing, in this instance, sets off a peculiar

kind of abjection, one that is triggered by the breakdown of boundary

between life and death, inside and outside, self and other.

The psychoanalytic notion of abjection has been

developed

by Julia Kristeva in her book Powers of Horror of 1980. Heavily based

on Lacanian psychoanalysis, the book defines abjection as the child’s

process of forcefully expelling what is part of itself. What is

abjected, however, can never be completely excluded, but remains part

of ourselves, and throughout our lives constantly challenges our

concepts of self-identity and integrity. According to Kristeva, the

corpse is the space in which borders between self and other are

erased, collapse, lose meaning. The corpse reminds us that death is

inevitable, but is not simply because it is a symbol of human

mortality. It directly infects our own living, violating our own

borders. Representing the epitome of abjection, we reject corpses,

but they are that from which we are ultimately unable to depart.

This print seems to materialise both the traumatic encounter with the

cadaver and its pervasive ability to pollute our perceptions. The

dead body, laying awkwardly on the left, is now forever lost. The one

standing, seemingly alive, repeats its own dissection by peeling away

its skin and exposing the insides of its abdomen (represented,

significantly, without any kind of anatomical accuracy). This figure

is in between life and death, a corpse that came back to life only to

die again. The bodies from Vesalius’ Fabric aimed to transform

anatomised bodies into categories of knowledge through their

insertion in classical landscapes, which remind viewers that

integrity and fragmentation are not in binary opposition but can

freely take each other’s place. Those of Valverde’s attempted to

produce a space in which the inherent contradictions of translating

the body’s physicality into representations could be explored.

This image, instead, seems to be doing something completely

different. The body is certainly not represented as an idealised

form, epitome of perfection and generator of norms and laws; it is

neither an attempt to reveal internal problems in anatomy as a

practice. It is, perhaps, a sombre suggestion that knowledge cannot

be acquired through accumulations of technical notions. Corporeal

unity, lost in dissection, cannot ever be recovered. Fragmentation is

absolute and inevitable.

In the limited space of this article, I aimed

to propose a new way of

looking at the anatomical series produced by Giulio Bonasone. The

entire collection would of course require a more detailed analysis

due to the large amount of peculiarities it contains, which are

perhaps unique in the context of early modern Italy. These images

seem to react to the complex cultural circumstances that surrounded

the study of the human body, in between dominant religious beliefs

and shifting philosophical thoughts, according to which the human

body could (and should) be analysed through practices until then

reserved to objects and elements from nature. The actual moment of

dissection, which was about to become a social ritual with its own

rigorous regulations, produced in spectators and executioners intense

emotive responses: when translating anatomy into image, these

responses were manifested in different modes. Generally, there was an

attempt to reconstruct some kind of bodily integrity despite – or

even because of, the violent laceration of the corpse (a laceration

that was both physical and psychic). In Giulio Bonasone’s

anatomical series, instead, the intent seems to be the opposite.

These images intensify the split between corporeal physicality and

personal identity, and replicate indefinitely notions of rupture,

doubling, fragmentation, materialising a creeping sense of morbid

abjection.

FOOTNOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AGAMBEN 2011

Giorgio Agamben, Nudities, translated by David Kishik and Stefan

Pedatella, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011

ALBERTI 1980

Leon Battista Alberti, De Pictura, edited by Cecil Grazyson, Rome:

Laterza, 1980

ANZIEU 1989

Didier Anzieu, The skin ego, translated by Chris Turner, London: Yale

University Press,1989

BARTSCH 1866

Adam von Bartsch, Le Peintre Graveur, Vienna: Leipzig J. A Barth,

1866

BECK 2015

David Beck, Knowing Nature in Early Modern Europe, London: Pickering

and Chatto, 2015

CARLINO 1999

Andrea Carlino, Books of the Body, London and Chicago: University of

Chicago Press, 1999

CAVANAGH, FAILLER, JOHNSTON HURST 2013

Sheila L. Cavanagh, Angela Failler, Rachel Alpha Johnston Hurst,

Skin, Culture and Psychoanalysis, Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2013

CUMBERLAND 1793

George Cumberland, Some anecdotes of the life of Julio Bonasoni,

London: Printed by W. Wilson, Ave-Maria Lane, Row 1793

DACKERMAN 2011

Susan Dackerman, Prints and the Pursuit of Knowledge, New Haven and

London: Yale University Press, 2011

FERRARI 1987

Giovanna Ferrari, “Public anatomy lessons and the carnival: the

anatomy theatre of Bologna”, Past & present, No. 117, 1987, pp.

50-106

FOUCAULT 1994

Michel Foucault, The Order of Things – an archaeology of the human

sciences, London and New York: Routledge, 1994

GHIBERTI 1998

Lorenzo Ghiberti, I commentarii, Biblioteca nazionale centrale di

Firenze, Rome: Giunti, 1998

GINN, LORUSSO 2008

Sheryl L. Ginn, Lorenzo Lorusso, “Brain, Mind, and Body:

Interactions with Art in Renaissance Italy”, Journal of the History

of the Neurosciences: Basic and Clinical Perspectives, No. 17, 2008,

pp.295-313

KAY 2006

Sarah Kay, “Original Skin: Flaying, Reading, and Thinking in the

Legend of Saint Bartholomew and Other Works”, Journal of Medieval

and Early Modern Studies, No. 36, 2006, pp.35-73

KLESTINEC 2005

Cinthya Klestinec, “Juan Valverde de (H)Amusco and Print Culture”,

in Zergliederungen - Anatomie und Wahrnehmung in der Frühen Neuzeit,

Frankfurt: Zeitsprünge, 2005

KRISTEVA 1982

Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror, translated by Leion S. Roudiez, New

York and Chichester: Columbia University Press, 1982

KUSUKAWA 2012

Sachiko Kusukawa, Picturing the book of nature, Chicago: University

of Chicago Press, 2012

MASSARI 1983

Stefania Massari, Giulio Bonasone, Ministero per i beni Culturali e

Ambientali, Rome: Quasar, 1983

PARK 1994

Katharine Park, “The Criminal and the Saintly Body: Autopsy and

Dissection in Renaissance Italy”, Renaissance Quarterly, No. 47,

1994, pp.1-33

PARSHALL 1993

Peter Parshall, “Imago Contrafacta”, Art History, Vol. 16 No.4

December 1993, pp.554-579

SAN JUAN 2008

Rose Marie San Juan, “Restoration and translation in Juan de

Valverde’s Historia de la composicion del cuerpo humano”, in

Rebecca Zorach, The Virtual Tourist in Renaissance Rome: Printing and

Collecting the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae, Chicago: University

of Chicago press, 2008

SAWDAY 1995

Jonathan Sawday, The Body Emblazoned: Dissection and the Human Body

in Renaissance Culture, London: Routledge, 1995

SCHULTZ 1985

Bernard Schultz, Art and anatomy in Renaissance Italy, Ann Arbor: UMI

Research Press, 1985

SMITH 2006

Pamela H. Smith, “Art, Science, and Visual Culture in Early Modern

Europe”, Isis, Vol. 97, No. 1, 2006, pp.83-100

WILSON 1987

Luke Wilson, “William Harvey's Prelectiones: The Performance of the

Body in the Renaissance Theater of Anatomy”, Representations,

Special Issue: The Cultural Display of the Body, No. 17, 1987,

pp.62-95

SITOGRAPHY

POWELL 2011

Alison Powell, “Self-Dissecting Devotional Bodies, Torture, and the

State", Shakespeare en devenir- Les Cahiers de La Licorne, No.

5, 2011, URL :

http://shakespeare.edel.univpoitiers.fr/index.php?id=572

WOLF 2007

Susan Wolf, "Juan Valverde de Amusco" from the website The

Boundaries of the Body and Scientific Illustration in Early Modern

Europe, URL:

https://web.archive.org/web/20070310133207/http://www.bronwenwilson.ca/physiognomy/pages/biographiesall.html

|